410 U.S. 113 (1973)

Jane ROE, et al. v. Henry WADE, District Attorney of Dallas County.

Argued Dec. 13, 1971.

Reargued Oct. 11, 1972.

Decided Jan. 22, 1973.

“Clearly, therefore, the Court today is correct in holding that the right asserted by Jane Roe is embraced within the personal liberty protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Roe v. Wade is a landmark Supreme Court case revolving around the hot-button topic of abortion and its moral, ethical and biological implications. Decided in 1973, it has long since been a standard of the affirmation of human rights and a long-standing subject of debate.

From its first few seconds as a petition on appeal to its countless appearances as a precedent in countless cases following its decision, Roe’s influence on the public sphere is undeniable.

A greater understanding of Roe’s significance and legacy is a must, especially given the legal complications surrounding Texas’s current heartbeat bill.

Mirroring the public political landscape of the early 1970s, the contemporary debate concerning Texas and abortion has reached nationwide attention as a possible overturning of Roe—thus generating further discussions on its reverberating consequences on abortion, privacy and subjective morality’s perceived power over trained medical competency.

From students in the WJ building to protesters across the street, everyone seems to have an opinion on the landmark 1973 ruling in Roe, and yet few people are actually well-versed on the details of the case.

To preface—this is a very liberal, pro-choice article that aims to disseminate topics such as the biological basis behind pregnancy, the Roe ruling, the inclusivity of language and the significance of personal context.

***

I. Brief

(Note: “I. Brief” is meant to be a summary of many relevant subject matters—appropriate background on basic biology, the case ruling of Roe—to contextualize the situation and provide necessary background information, and thus can be omitted in a cursory informed read of this article.)

“She claimed that the Texas statutes were unconstitutionally vague and that they abridged her right of personal privacy, protected by the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth and Fourteenth Amendments…”

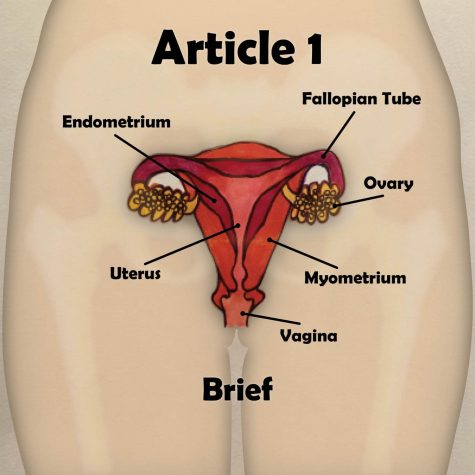

Part A. The pregnancy

The most basic and often misunderstood component of the abortion debate is pregnancy itself. The AP Biology curriculum provides a comprehensive, while somewhat bare-bones, explanation of this process, recounted below.

Pregnancy begins with two haploid cells—an egg and a sperm—which each contain half of the 46 chromosomes of DNA (23 chromosomes each) needed to produce a viable diploid cell that grows throughout pregnancy. All of the eggs that an AFAB (assigned female at birth) has in their ovaries are present when that person is born, and all of the sperm that an AMAB (assigned male at birth) has is replenished roughly every two months, with new sperm cells being produced every day.

Starting in their preeteen/teenage years and repeating roughly every 28 days, AFABs go through a menstrual cycle which moves one or (rarely) more eggs through their fallopian tubes to their uterus for possible fertilization. The first phase of the menstrual cycle is the follicular phase. The first four or so days of this are when the actual process of menstruation takes place—the uterus sheds the past cycle’s thickened uterine lining, assuming that an egg was not fertilized during that past cycle.

The next five days are when the uterine lining begins to thicken again to prepare for the next egg to travel from the ovaries through the fallopian tubes and into the uterus. Days 10 through 14 are roughly when the person has the highest chance of getting pregnant, as the egg descends through the fallopian tubes; this process of ovulation ends roughly on day 14. Days 15 through 28 are the luteal phase, where the egg is either fertilized and implants into the uterine lining or is reabsorbed by the body; the thickened uterine lining also prepares to be shed during the next cycle’s menstruation at this time. And then, the process repeats.

Mid-menstruation cycle, roughly 24 hours before it is fertilized, the egg cell present during the current menstrual cycle completes meiosis, becoming fully formed as a mature oocyte. If an AFAB and AMAB have sexual intercourse, the latter’s sperm will travel through the vaginal canal and uterus to the fallopian tubes in order to try to fertilize the egg; this may take several days as ovulation takes place. When the sperm fertilizes the egg, the two join to form a zygote, a single-celled organism which has the 46 necessary chromosomes (in the absence of a chromosomal deletion or addition) for viability, or the ability to survive. The zygote continues through the fallopian tubes until ovulation is complete, and implants into the thickened uterine lining, where it will grow for the next 40 or so weeks.

If it does not implant in seven days, the zygote will die, resulting in a pregnancy not progressing even though the egg has been fertilized. If this occurs, the AFAB will experience menstruation as the uterine lining is shed in what is technically the second week of pregnancy.

Various chemical changes later, the zygote is ready to go through—and, in fact, technically already going through—the process of gestation, growing into an embryo (marked by the formation of organs) which can eventually be born. This process is divided into three equal periods, or trimesters, and is overseen by the pregnant person’s attending physician—usually an obstetrician who is licensed by the state and able to determine the risks and progression of pregnancy, as well as the need for various medical procedures, such as an abortion.

In the first trimester, the embryo begins to take basic shape. For the first few weeks, the uterine lining takes care of the waste and nutrients from the embryo, until the placenta develops to handle the nutrient and waste requirements of the embryo by carrying them through the pregnant person’s bloodstream and liver. By the seventh week of pregnancy, otherwise known as the gestational age—the fifth week of development after fertilization, or the fetal age—the embryo has formed limb buds, eyes, a heart and a liver, and can be termed a fetus three weeks after this point, at 10 weeks gestational age. By the end of this trimester, the fetus is about two inches long, and most of its organs don’t yet function—if it were to be born, it would not be able to survive.

In the second trimester, the fetus continues its growth and begins its first movements. Its organs are still generally nonfunctional, but are more developed than in the first trimester. By the end of this period, the fetus is roughly 12 inches long. Towards the end of the second trimester, the fetus is sometimes able to achieve “meaningful life”—the fetus is able to survive more independently if it is born, with less need for medical intervention as gestation continues and organs develop.

In the third trimester, the fetus grows to roughly 20 inches long, and gains significant weight. This is the time at which the fetus grows the fastest, though the organs and bodily systems of the fetus still do not develop fully. Most systems develop until birth, and some, like the nervous system, continue to develop even after the fetus is born. The pregnant person is also usually the most uncomfortable during this trimester. They are at risk of incontinence, intestinal blockage, pre-eclampsia (high blood pressure and damage to their other organs) and blood clots, especially in their legs.

When the fetus is at roughly 40 weeks gestational age, the pregnant person gives birth. This can happen naturally, or be medically induced by the attending physician if the pregnant person experiences discomfort or danger to their health and quality of life. Birth can be risky, especially if the pregnant person’s access to medical care is limited, and result in injury or death from various complications. These include, but are not limited to, blood vessel tears and hematomas, blood clots and eclampsia—newly and rapidly developing seizures and coma.

Due to the varying viability of the fetus throughout gestation, there are various “theories of life” which attempt to solidify the moment when life begins. Some people believe that life begins at conception, when the zygote first forms, even though it is unable to survive outside the uterus. Others believe that life begins when the fetus reaches viability (at 24 weeks gestational age in the US, or after roughly six months of pregnancy) and is able to survive in some way, or even later when the fetus is able to have “meaningful life” outside of the uterus. Still others believe that life begins at birth, when the baby leaves the uterus and takes its first breath.

Part B. Roe v. Wade

These interpretations of the “theory of life” are key to understanding the decision made in Roe. This case centers on Jane Roe, a pregnant single woman from Texas whose attorneys filed a suit against her local district attorney, Henry Wade, claiming that Texas’ ban on abortions that weren’t strictly necessary to save the pregnant person’s life was unconstitutional. A basic summary of the final court ruling from that case is as follows:

A statewide blanket ban on all abortions without regard to the viability of a fetus and the other factors of the case, such as the health and quality of life of the pregnant person, violates the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment.

For any pregnancy that is in the first trimester or right at its end, the state may not dictate whether a pregnant person can have an abortion. The pregnant person’s ability to have an abortion is between them and their attending physician.

After the first trimester but prior to viability, if a state can make an acutely compelling argument as to why continuing the pregnancy is beneficially related to the health of the pregnant person, or is not explicitly necessary to maintain the good health and quality of life of the person in any way, they may restrict the pregnant person’s access to an abortion. Unless they can argue this in a reasonable way, they may not restrict their access.

Once the fetus has reached viability and can have a “meaningful life” outside of the uterus, the state may regulate—or, in more extreme cases, prohibit—a pregnant person from getting an abortion, unless a physician deems an abortion necessary to beneficially preserve the the health and quality of life of a pregnant person. The state may only define a physician as a medical professional currently licensed by that state.

As the fetus passes initial viability and approaches full term, the state may place more restrictions on abortion access, as long as they can provide adequate basis as described above. A physician may independently decide whether an abortion is justified as long as “important state interests” don’t interfere in this way. Restrictions aside, it is completely up to the physician and the pregnant person to decide on whether the pregnancy should be aborted, because an abortion is at its core inherently one’s private medical choice, and people have a constitutionally guaranteed right to medical privacy.

A state may not use their particular “theory of life” and when it begins in order to override the rights of pregnant people. That is, a fetus’ “right to life” does not take precedence over the rights to life, privacy and self-determination of the person carrying it, no matter the pregnant person’s state of residence.

While a state has an interest in preserving the health and life of both a pregnant person and a fetus, the pregnant person’s health and life generally take priority over the fetus.’ However, except in cases of medical necessity and preservation of health and quality of life for the pregnant person, once the fetus reaches viability, the health and life of the fetus have more sway—but still less sway than that of the pregnant person. The authority may only stop an abortion from taking place for a viable fetus (already by far a minority of all abortions) if a continued pregnancy poses no risk to the pregnant person’s life or health.

To summarize: in the final ruling on Roe, the Supreme Court upheld a pregnant person’s right to have an abortion, as deemed appropriate by their attending physician, while taking into account the biological development and viability (or, in most cases, the lack thereof) of the embryo or fetus.

Part C. Doe, Planned Parenthood and the Texas Heartbeat Act

A similar decision, on the same day of Roe’s decision, was reached in its lesser-known companion case Doe v. Bolton, which dealt with an abortion law in Georgia.

This debate was once again explored in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which examined a Pennsylvania abortion law and, like its predecessors Roe and Doe, struck down further state-established restrictions on people seeking abortions. Planned Parenthood upheld Roe’s precedent but replaced its trimester-based framework with a system based more explicitly on fetal viability.

Most recently, the ruling in Roe has come to be debated because of the 2019 Texas Heartbeat Act, a law in Texas that prohibits abortion of an embryo—not even a fetus—once it has a detectable heartbeat, at roughly six weeks gestational age; it also makes abortions by attending physicians punishable by up to 10 years in prison. This makes abortion illegal for non-viable fetuses (younger than 24 weeks gestational age) which cannot survive outside of the uterus. For context, at six weeks gestational age, the embryo has only just developed the beginnings of a brain and spinal cord, and is still missing almost all of its organs and limbs. In terms of size, it is ⅛ to ¼ of an inch long—roughly the size of a grain of rice.

Moreover, most people only notice that they are pregnant around six weeks gestational age, when they have missed a menstrual period. Since people obviously can’t have an abortion if they don’t know that they’re pregnant, prohibiting abortion past roughly six weeks gestational age removes their ability to have an abortion altogether.

The Texas Heartbeat Act (as well as similar bills in Georgia and multiple other states) has an additional horrifying implication—the potential criminalization of miscarriage, when a pregnancy randomly ends before 20 weeks gestational age due to external factors outside of the pregnant person’s control (genetic mutations to the fetus, physical injury, etc.).

In addition to ending the fetus’ gestation, miscarriage can cause significant damage to the pregnant person’s health, or even put their life at risk. Even though the pregnant person would not be at all at fault for their own miscarriage, the miscarriage could be treated as a “spontaneous abortion” which (falsely) resulted from a lack of care or caution on the pregnant person’s part, and therefore might be argued to be purposeful.

The abuse of this logic could be used to target minority communities—for example, AFABs of color and especially Black AFABs—who on average have to face higher rates of domestic violence, economic inequality and inadequate medical care, and as such are more likely to have a miscarriage.

This rampant potential for discrimination becomes apparent when we realize how the act is actually enforced: by giving private citizens free reign to initiate lawsuits on anyone who assists in an abortion.

Based on the ruling in Roe and its successors, many have called the Heartbeat Act unconstitutional; suits against the Act have progressed to the State Supreme Court. These suits have not been taken to the federal Supreme Court as of yet, but the federal Supreme Court has affirmed the right of these suits to take place on the state level.

However, the federal Court has also refused on numerous occasions to allow these cases to be tried on a federal level at all (most recently on Jan. 20th), keeping Roe’s fate undecided.

“…Roe purported to sue ‘on behalf of herself and all other women’ similarly situated.”

***

II. Biological implications of Roe

“The Does alleged that they were a childless couple; that Mrs. Doe was suffering from a ‘neural-chemical’ disorder; that her physician had ‘advised her to avoid pregnancy until such time as her condition has materially improved’…”

It is very clearly established in the Roe ruling that deciding to have an abortion “in all its aspects is inherently, and primarily, a medical decision,” and one which rests on a licensed attending physician to ultimately make, with the best interests of their pregnant patient in mind.

Though the decision to have an abortion is harrowing and traumatic—as evidenced by the very conflict of opinion on the topic, as well as the harsh medical repercussions of both pregnancy and abortion—ultimately, a person’s right to an abortion is not an issue of morality. It is an issue of medical practice and simple scientific fact.

Even if morality were applicable in this case, the ruling in Roe safeguards against its overuse. As stated above, the state may not use their own “theory of life” to override a pregnant person’s right to privacy and medical self-determination. Even if the state proffers that life begins with conception, the threshold for abortion restriction is viability, 24 weeks (i.e. six months) after this point.

Due to the vast developmental differences between a zygote at conception and a fetus at 24 weeks gestational age, it is completely irrational to compare the two—only one has functional organs and some degree of survivability outside of the uterus, and it isn’t the zygote.

Up to a certain point, the zygote really is just a miniscule clump of cells which cannot think, move or even discard waste on its own. To place this on par with a living, breathing, adult human being who is put in physical and mental distress throughout pregnancy and birth is almost absurd.

Of course, the life and health of both the fetus and the pregnant person must be considered before an abortion is performed. However, as mentioned before, the ruling indicates that prior to viability at 24 weeks gestational age, a fetus’ life and health are far lower in priority than those of the pregnant person. 91% of abortions occur before the fetus reaches 13 weeks gestational age, more than two months before viability and just three short weeks after the fetus has been reclassified as a fetus at all—it has just barely developed the organs that it needs to live, and still cannot survive on its own because these organs are generally nonfunctional. An even higher percentage of abortions occurs before the fetus is actually a fetus. In a medical, legal and scientific sense, the vast majority of abortions do not get rid of babies—they get rid of unwanted excess intra-uterine tissue.

It is logical that there should be restrictions placed on the abortion of fetuses that are approaching or have achieved viability when an abortion is not strictly medically necessary or beneficial. That is, having an abortion for convenience’s sake becomes ethically questionable when the fetus is able to live outside of the uterus. The ruling in Roe accounts for this, allowing states to progressively restrict access to abortion after the fetus reaches viability. However, it is important to remember that pregnant people generally don’t simply decide to abort their unborn child after being pregnant for more than six months (past 24 weeks gestational age, after the fetus has become viable).

Almost all late-term abortions are being conducted as a last resort, out of medical necessity—if the pregnant person is at risk of serious injury or death from continued pregnancy. This necessity is determined by a state-licensed attending physician, as Roe specifies that it should be. The physician’s role is also intuitive—who else but a licensed medical professional can determine the necessities and risks of a medical procedure? Certainly not a layperson.

Conclusively, the ruling made in Roe, and repeatedly upheld in Doe and Planned Parenthood, makes perfect biological sense. It accounts for how well the fetus can survive outside the uterus, how well the pregnant person can survive without an abortion and how the potentially conflicting interests of these two parties can be successfully moderated from a moral standpoint while keeping medical and scientific basis at the forefront of the decision-making process.

“…and that, if she should become pregnant, she would want to terminate the pregnancy by an abortion performed by a competent, licensed physician under safe, clinical conditions.”

III. Re-examining Roe

“The fetus, at most, represents only the potentiality of life…”

Having established the clear biological reasoning behind the ruling in Roe, it becomes apparent that many anti-abortion advocates often make logical fallacies and overall misconceptions when making their cases against abortion. We aim to clarify as much of them as possible below.

Part A. What is life?

One frequent point made is that life begins at conception. However, as discussed in the previous article, this is neither definite nor scientifically true. Because there is no absolute “theory of life”—assuming one ignores the standard of viability that has been repeatedly upheld in contemporary court (itself a subjective measure developed as a compromise to conflicting political agendas)—it is inherently wrong to say definitively that conception marks the beginning of life.

Moreover, the scientific definition of life itself conflicts with the choice of conception as the beginning. Britannica defines life within a physiological and autopoeic context as “any system capable of performing functions such as eating, metabolizing, excreting, breathing, moving, growing, reproducing and responding to external stimuli,” and doing so more or less independently or self-sufficiently, without specific guidance from an external source.

At one point or another, an embryo or fetus cannot perform nearly all of these functions.

Prior to four or five weeks gestational age, the embryo doesn’t have a placenta to “eat” or “excrete” without using exclusively the pregnant person’s bloodstream and liver. Neither of these functions can happen in a more traditional sense until birth; breathing cannot occur before birth at all, as there is no air to breathe in the uterus. While the cells of the embryo or fetus might “reproduce” as it grows, the fetus itself cannot reproduce until after birth.

A fetus first responds to any stimuli—usually sound—at 16 weeks gestational age, and will only respond to the voice of its biological AFAB parent multiple hours after birth. Movement is the last to develop, with the fetus’ very first movements occurring between 18 and 20 weeks gestational age. All of these occur before viability, but far after conception and the detection of a heartbeat, and do not entail “meaningful life”—the fetus, while technically alive by 20 weeks gestational age, would not be able to survive long outside the uterus, even with intensive medical intervention and support.

To take the idea of life at conception to a slightly more ridiculous level, if two haploid cells joining together to make a zygote indicates their “aliveness” as a single-celled organism, do the two haploid cells existing separately, also as single-celled organisms, also constitute life? If yes, are all future children alive as soon as their AFAB biological parent is born? Do these children die every day inside an AMAB’s testicles? Is masturbation by an AMAB technically infanticide because the ejaculated sperm cells inevitably die? These are the kinds of questions we would ask ourselves if we placed less weight on biology than on moral detail.

Part B. The likelihood of conception

Another point often made is that conception is unlikely — the process of creating haploid cells like eggs and sperm is “special,” and combining these two “incomplete” cells into a “complete” zygote is somehow miraculous. Right off the bat, this presents a flaw—basically all organisms which undergo sexual reproduction (which is to say, an estimated 99.9% of all eukaryotes, organisms whose cells have a distinct nucleus) also undergo meiosis, the process by which egg and sperm cells are made.

The fact that meiosis is a separate process from mitosis—by which other cell types are made—doesn’t make it more magical or unique. As such, it becomes clear that sexual reproduction itself isn’t at all wondrous.

Additionally, conception is actually quite likely, and the barriers to it have been greatly minimized for the majority of people who do not face fertility issues; for those that do, medical treatment also exists to improve the odds of conception. Even without these medical marvels, the human reproductive system is built to be fairly efficient.

Following these claims is the commonly-made assertion that sperm need to go through an arduous three-day journey for conception—but the “journey” is often actually much shorter. Moreover, it is less of a journey and more of a waiting period as the sperm enter the fallopian tubes and wait for three to five days, in conditions specially designed to keep them alive, for the chemical signal that indicates ovulation has begun and the egg is most susceptible to fertilization.

Also, the fact that millions of sperm cells are released every time an AMAB ejaculates compensates for the eventual death of many of the cells, so many still reach the egg to attempt conception in the average semi-ideal scenario.

More specifically, even though only 1 in 14 million sperm cells reach the egg to fertilize it, one ejaculation by the average AMAB produces roughly 280 million sperm cells. Assuming that the AMAB ejaculates only once during sexual intercourse, and does not expel any excess sperm (pre-ejaculate, etc.), around 20 sperm cells out of these hundreds of millions would survive to attempt fertilization, and only one of them is necessary for conception. As such, one bare-minimum ejaculation, producing far less sperm than most AMABs actually do, is enough to impregnate one AFAB as much as 20 times over in ideal conditions.

As mentioned, this likelihood of conception is actually much higher than presented in the prior article. According to the BBC, the minimum risk of pregnancy after one instance of sexual intercourse is roughly 20% (and 20/100 is a far cry from 20/280 million), and for most people who regularly have sexual intercourse, 85 of every 100 will get pregnant within a year.

In fact, high-school health class tells us (a separate issue entirely) that abstinence is the only way to completely prevent conception, and we can see how well that’s gone for the nearly eight billion people on this planet, and the roughly 100 billion people who have ever lived and reproduced.

Part C. Uniqueness as biological justification

A third major point often emphasized is that all embryonic and fetal life must be protected from abortion because their life is unique. In short, it is both morally and biologically wrong to “end the life” of a potential organism which has not only gone through difficulties to be conceived, but has also been created as “one-of-a-kind.”

Objectively, the idea of “uniqueness” isn’t really supported by biology itself. Scientifically, every probability of genetic combination (8.4 million possible such combinations) can be predetermined and explained—that’s the whole point of the entire field of genetic engineering and counseling.

While 8.4 million may seem like a lot, this uniqueness isn’t actually as large as it is stated to be. A significant number of these 8.4 million combinations are non-viable, and the zygote created with these combinations will either have its pregnancy naturally terminated in miscarriage—in fact, it is estimated that between 70% and 80% of all miscarriages are due to embryonic chromosomal defects—or it will die shortly before or after birth. Alternatively, the fetus which grows from this zygote will be born with a chronic or terminal chromosomal defect, and will likely not be able to achieve the “meaningful life” that the ruling in Roe calls for, as it will need near-constant medical support and have an objectively miserable quality of life. As such, there are really fewer than 8.4 unique chromosomal combinations which can result in viability or “meaningful life.”

Thirdly, even the figure of 8.4 million combinations is insignificant when put in the context of today’s human population. As of January 2022, there are roughly 7.9 billion people living on Earth. This is just over 940 times more people than there are viable and non-viable possible unique chromosomal combinations. Therefore, if you measure “uniqueness” based on unique chromosomal combinations alone, there is a possibility that there are 939 people just like you.

Additionally, it is wrong to assume that uniqueness is decided only by genetics. Biopsychology indicates that people are equal parts “nature” and “nurture”—just as much as one is born a certain way, one is able to change based on external factors and influences. Because of this, one cannot quantify uniqueness as a purely biological occurrence. Indeed, even identical twins aren’t truly identical, and each is their own unique person. In short, one’s “unique” genetic combination isn’t any more special than one’s development of a unique personality, as human beings do.

That being said, it is clear that following the very foundations presented in the “uniqueness” argument, pregnant people are unique human beings, too. There is nobody else like them, so their preventable death due to lack of access to an abortion would be just as much of a tragedy—and, according to Roe and frankly common sense, more of a tragedy—than the abortion of the fetus that the person is pregnant with. Abortion exists as a medical procedure which is innately centered on the preservation of unique human life in the face of staggering cost, and it is high time for it to be recognized as such.

“…In short, the unborn have never been recognized in the law as persons in the whole sense.”

***

IV. The language of Roe

“Pregnancy often comes more than once to the same woman…”

Part A. Harry Blackmun

In all our discussions on abortion and parenting, we shouldn’t forget Roe’s own unwitting parent—Supreme Court justice Harry Blackmun. A Nixon-appointed justice who began his career as a Republican lawyer in the Midwest (as conservative and white as it gets), Blackmun soon began judgeship with a federal appellate court after a two-decade stint as an attorney. After another decade in court, he was then brought to the steps of the country’s highest after Nixon’s first two nominations were rejected by the Senate.

As mentioned, Blackmun was a lifelong Republican, holding Republican values and practicing Republican ideals, a surprising revelation given Roe’s frequent citation as the Supreme Court’s most liberal decision to date.

Blackmun, as a self-described conservative, disagreed with abortion on a personal level. This, however, was no issue for him—he saw abortion as a constitutional issue, casting aside his own moral dissent to craft the necessary foundation for what would soon become the most controversial decision in the Court’s history. He realized that his opinion and experience was rather irrelevant and so instead sought to embody a perspective that was not his own.

It is worth mentioning that Blackmun was heavily interested in medicine throughout his life—even considering going to medical school—and actually served as a legal counsel for Mayo Clinic’s Minnesota campus for several years. In fact, he relied on his experience and research methods from Mayo extensively when devising the theoretical framework and vital background while drafting the court’s decision.

Part B. Language today

To take a brief sidestep, the ever-evolving views of society on gender must be acknowledged in this debate so heavily steeped in an abject discussion of it.

Traditional definitions of “man” and “woman” have long since been under scrutiny in the public eye, and are in the process of deprecation as a new, more culturally inclusive language emerges. Roe was ruled at a time when paradigms of gender roles and expression, while beginning to be reexamined, still held mass sway as the reigning interpretations of the human experience—but we are not 1973.

Throughout this article, we write about “AFABs,” people assigned female at birth, and “AMABs,” people assigned male at birth. In our continued discussions on abortion, pregnancy and biology, we have to remain cognizant of the fact that there is no actual gender binary (itself a largely arbitrary social construct) and cannot presume to have such when we’re navigating through such a socially intensive, sensitive topic like this.

It seems almost laughable to say “penis-having person” or “uterus-having person,” but it shouldn’t be.

Uteruses aren’t exclusive to people identifying as women, nor do women have to have uteruses. In a historic first-of-its-kind event, trans man Thomas Beatie made headlines in 2008 when he gave birth to his first child, the first-ever case of a legally-recognized male undergoing pregnancy and giving birth.

Surveys such as those by the Williams Institute have estimated that there are around 1.4 million transgender people in the US alone, a proportion with a surprisingly low standard deviation when considering state differences. In fact, Maryland is on the lower end of this range even when compared to Republican strongholds like Alabama, South Carolina and Texas, with only about 0.37% of its population identifying as trans against the 0.40–0.50% range of the Sun Belt states, according to the World Population Review.

Increasingly inclusive language and practices are spurred by national and even international policymakers, organizations and leaders of the LGBTQ+ community. The American Medical Association itself is one of these agents of change, recommending the removal of the “sex” designation on birth certificates. Contemporary physicians and medical practitioners have begun using gender-neutral/inclusive terminology, such as “pregnant people” and “perinatal” and “bodyfeeding/chestfeeding,” as a way of systematically adopting more inclusive language to better fit a changing society.

Terms like “pregnant person” and “AFAB/AMAB” feel awkward and out-of-place in both informal and professional contexts, but that is only because these terms have only just recently been gaining traction as the beginnings of a permanent social upheaval—that itself goes hand-in-hand with and, at least partially, traces back to Roe—against the gender binary.

“…and in the general population, if man is to survive, it will always be with us.”

V. Context matters

“In view of all this, we do not agree that, by adopting one theory of life, Texas may override the rights of the pregnant woman that are at stake…”

Reflecting on all of this, it becomes clear that context matters. While arguments like this are largely content-driven, and have to be, they cannot preclude the contexts by which each new addition to the debate is made.

This is said not to be derogatory, but to highlight the reason why these debates began in the first place—to finally acknowledge the people whose voices have been suppressed for so long.

But, isn’t that why we fight for human rights in the first place, to preserve the morality, equity and integrity of society? To ensure that the liberties of every living person to, well, live is maintained?

It is as such that we believe that their voices, those people whose voices have long been suppressed, matter more.

Marginalization with respect to pregnancy and abortion is incredibly complex, due to the sheer number of social, economic, and political factors that play into these processes. Generally, it can be defined as AFABs who lack adequate social and medical support, often those who are economically, socially, or politically restricted from this support. This can take many forms: an underpaid waitress who can barely afford rent, a long-haul trucker gone from home for weeks at a time (and yes, non-men can be truck drivers) or a scared high-schooler who can’t even sit still long enough in Honors Chemistry to do a lab correctly. For each of these, their age, relative wealth and schedule flexibility might add to further systemic issues, such as racism, sexism or xenophobia, to further restrict not only their access to prenatal but also postnatal care. Because they and their child might be put through life-altering challenges due to such societal inequality, it is illogical to broadly claim that every child’s birth is a “miracle.”

Because it’s not a miracle. Not for a lot of people.

By very broad contrast, a cisgender man will never have as much personal stake in the debate on abortion as an AFAB. All other factors aside—religious preference, moral standpoint, scientific justification—a cisgender man will never have to experience a pregnancy or abortion on his own, and so the need for an abortion will never impact his own bodily autonomy.

It is our belief that as such, he should not have more control or sway over the accessibility of abortion, and by extension bodily autonomy, than people who might actually need to go through this medical procedure. Taking account of other factors—wealthier and white cisgender men will never be negatively impacted by the medical, socioeconomic and racial biases which restrict abortion access for poorer and nonwhite AFABs—it becomes clear that the average cisgender man is not marginalized in the abortion debate.

It is therefore, we think, in his best interest to support the voices of AFAB people who might actually need abortions or face more significant barriers to getting them, making sure that they get the medical care that may well save their life, instead of speaking over them. Because in the end, it is they who experience the pain, the suffering, the miracle of bringing life into this world. It is their voices who need to be uplifted—the voices that cry out in the pain of labor, that sing soft lullabies while cradling their newborns, that forever echo down the halls of the hospital after a pregnancy gone wrong.

“…We repeat, however, that the State does have an important and legitimate interest in preserving and protecting the health of the pregnant woman, whether she be a resident of the State or a nonresident who seeks medical consultation and treatment there.”

VI. The consequences of birth

“The detriment that the State would impose upon the pregnant woman by denying this choice altogether is apparent. Specific and direct harm… a distressful life and future [and] psychological harm… There is also the distress, for all concerned, associated with the unwanted child, and there is the problem of bringing a child into a family already unable, psychologically and otherwise, to care for it… [and] the additional difficulties and continuing stigma of unwed motherhood…”

The nine-month process of pregnancy and the minutes immediately following birth are extremely complicated and highly emotional, and external factors can place both the parent’s and the baby’s lives at risk of extreme danger. When high-risk individuals are forced to go through with their pregnancy without their consent, this can cause irreparable emotional harm.

Some concede and push through with an unwanted pregnancy, and the combination of a low socioeconomic status and poor living factors can only serve to impede the fetus’s development inside the womb, and can cascade into a range of other issues as further complications throughout the pregnancy that affect both the pregnant person and the fetus arise.

Others resist this, leading them to seek alternative methods of termination—taking dangerous combinations of medication, self-harm or unlicensed abortion procedures to prevent birth. Anti-abortionists deride these people’s desperation to “kill their children,” but what else can be done when the pregnant person’s own life is at stake? Anti-abortionists fail to consider how distressing it is to have an unwanted pregnancy, especially when the person is impoverished, in an area of high infant mortality or just generally understands that they are neither ready nor fit to have a child.

Simply “putting the child up for adoption” is, in many cases, out of the question. Whether it be because of a disapproving culture, the lack of potential places that can take the baby or general conscience, adoption is a grim and hazy reality.

This is especially true in the US—there is very little funding and care placed on maintaining the infrastructure of adoption, leading it to become an inaccessible privatized industry. Many unwanted children are then funneled into the foster care system, which receives even fewer resources and recognition. Due to high rates of housing inaccessibility and other support issues which are exacerbated by unwanted children “aging out” of the system when they turn 18, this has long been referred to as the “pipeline to homelessness.” In a sense, these unwanted children are often effectively doomed to a lifetime of struggle and inequality.

This further fails to take into account the emotional well-being of the new parent following a birth or even an adoption; who would be willing to part ways with their new child, even in the face of real danger that plagues them in the years ahead?

Moreover, is it equitable to force a birthing parent to separate from their child so soon after birth?

Most domesticated animals cannot be separated from their parents for weeks and months following birth due to the increased risk of illness, injury and death; a lack of research and regard for how this applies to human children places them at a unique disadvantage if they are to be removed from their birth parent.

These are just a few of the post-birth repercussions of the inaccessibility of abortion. Their overarching negativity and long-lasting consequences in turn make abortion more and more favorable.

“…All these are factors the woman and her responsible physician necessarily will consider in consultation.”

VII. Conclusion

Roe v. Wade was a court case that, while submerged heavily in biological implications, was much more than that—it was the attempted resolution of a long-standing debate on human rights. It not only defined a baseline framework for a lifesaving medical procedure, but also resolved issues pertaining to an individual’s right to privacy both in and outside of medicine.

From these discussions, it is made clear that abortion must stand, given its status as a critical medical decision made on the basis of countless complex factors that echo far beyond the black-and-white crises of morality presented in its detractors.

It is from here that we condemn the US Supreme Court’s refusal to bring the cases involving the Texas Heartbeat Act to the federal level, seeing it as a blatant denial of the fundamental rights that have been so constitutionally enshrined for nearly half a century. While there are those who seek to preserve Roe’s ruling both inside the Court (we thank Associate Justices Sotomayor, Kagan and Breyer for their work within a group that seeks to silence their own voices) and out of it (Planned Parenthood, the Jackson Women’s Health Organization and President Biden), it is not enough.

People nationwide are responding to the Heartbeat Act. Transportation companies are providing financial and legal assistance to any drivers being sued because of the act. Protests are rallying in front of capitals and other hundreds of locations all over the country. Hacktivist and whistleblower groups are bringing anti-abortion organizations under fire in the public sphere.

But again, it is not enough.

If the Texas act remains standing, it would without a doubt summon a nationwide political coup as other states scramble to adopt the Act’s unprecedented language and convoluted enforcement system to other issues—from gun control (which a California governor has notably pledged to do) and drugs to pornography and propaganda, questions being raised by legal scholars, academics and even policymakers in the wake of the Supreme Court’s errant decisions.

There’s no telling what the full repercussions of this could be.

Without federal protections securely in place to protect the rights affirmed in Roe and its successors, various states—not just Texas—have already begun their work. Florida, South Dakota, Nebraska, Minnesota and Wyoming are just the beginning. The Guttmacher Institute even estimates that should the Supreme Court completely overrule Roe, over half of the states in the country would immediately issue total or near-total bans on abortion.

Say that Roe is overturned. Say that Texas becomes the flagship for a wave of anti-abortion legislation. Say that, somehow, this contrived vernacular remains solely in this specific issue. Is the anti-abortion, the “pro-life,” agenda finally fulfilled?

The answer is no.

Where are the statutes in these laws that require hospitals to give free medical care before or following a “successful” birth? Is the state going to pay for the $15k it takes to give birth, let alone the $150k for a two-week hospital bed rest for the parent and a separate $200k bill for the baby’s own NICU stay? Is the state going to pay the full amount for every parent—and is it going to limit this privilege to tax-paying residents with citizenship and deny coverage to everyone else there, ignoring the DREAMers, undocumented immigrants and legal aliens in places of much higher risk?

Where are the statutes that give many years’ worth of significant financial assistance to these new parents? There’s a reason why people most in need of abortion procedures are the same people who are unable to access contraceptives to prevent the need of an abortion in the first place, and it’s not because they’re well-off. Is this financial assistance going to take place as an online form on a crappy government website as well, effectively blocking people who don’t have access to modern technology or are illiterate or any other possible disadvantaged demographic from getting this assistance?

Where are the statutes that provide these new parents access to resources, from food to baby clothes to daycare, that are necessary for a proper living environment? A working parent with two blue-collar jobs and crushing debt has neither the time nor the money to raise their new baby.

So, adoption?

If so, where are the statutes that pledge to give more funding to adoption agencies, to provide more experienced caretakers and psychologists that work in this field, to create better foster care systems? This child is going to need all the help they can get, and will live their life knowing that they weren’t wanted—knowing that their parent didn’t have the luxury of being able to want them.

As it turns out, the same people who use their power to hurt reluctant parents instead of assisting new ones—the Ted Cruzes and Jason Raperts, Amy Barretts and Brett Kavanaughs of the world—are the same people who can afford to burn hundreds of thousands of dollars on overlong hospital stays and way-too-expensive baby clothes and the magical, magical baby formula. And that’s why we don’t see any of these statutes in place to go along with their baby-saving laws. It doesn’t actually matter to them what happens to these new parents and their new children, as long as they can pat themselves on the back for a job well done and add up another mark on the “lives saved” counter.

And it remains to be seen what happens long-term to systematic inequality in this declining nation.

“It is so ordered.”

Laws applied—U.S. Const. Amend. XIV; Tex. Code Crim. Proc. arts. 1191–94, 1196.

Presiding Chief Justice: Warren E. Burger.

Majority opinion by: Blackmun, joined by Burger, Douglas, Brennan, Stewart, Marshall, Powell.