Should be bumped

Lizzie Kotlove

Imagine sitting in class and getting your last test of the quarter returned, just to see that your average in the class is now only a tenth of a percent away from the letter grade you had been working so hard for. You go up to your teacher and ask if there’s anything you can do to get your grade up, and either you get lucky, or you’re stuck feeling regretful, knowing that a minor mistake earlier in the quarter cost you a whole letter grade.

From my experience, seeing my grade so close to the next letter can be even worse than performing poorly. You were so close but now can’t do anything about it. While I completely understand why a teacher would say no to such a large request , I feel that an issue that presents itself is some teachers and courses are more lenient about grades, while others can be much stricter.

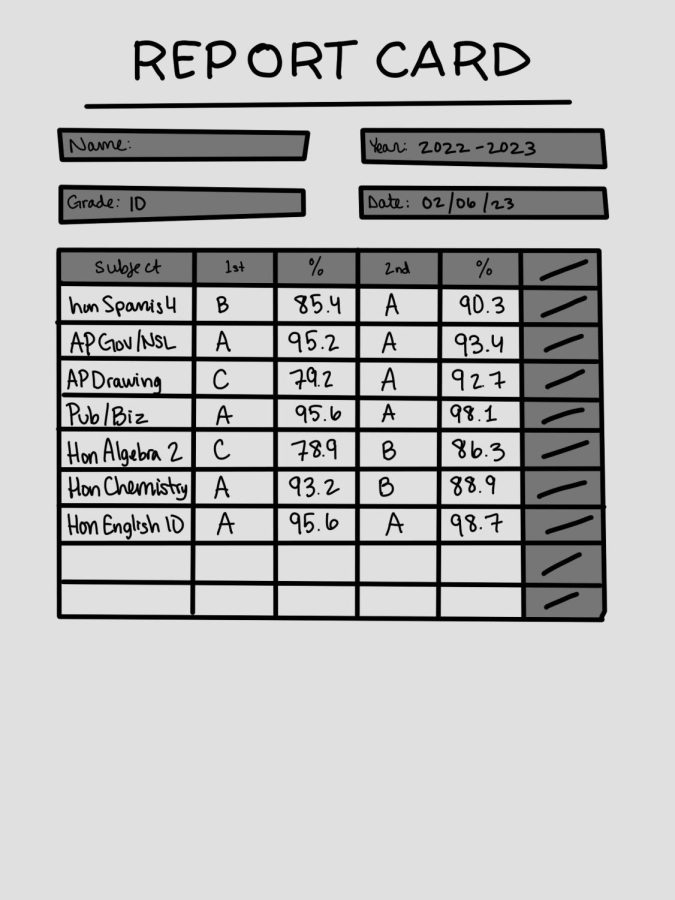

Understandably, many teachers stick to the grading system we have and are usually not prone to bumping grades. In Montgomery County, because of the semester grading system, someone in a class who ends up with an 80% first quarter and a 90% second quarter ends up with an A average for the semester, as opposed to someone who ended with an 89.25% both quarters will end with a B overall. I think that semester grades heavily contribute to teachers not wanting to bump up grades because they want you to keep working hard in the class the next quarter. These are the rules, but I believe that sometimes there are exceptions to the rules, which can make bumping up a grade valid.

In no way am I suggesting that a student who did not participate, did not complete assignments or frequently missed class should be able to get their grade bumped. However, if a certain student has worked hard enough and shown dedication, I think a teacher should be able to give them less than half of a percentage back. For instance, in some classes, teachers track and reward classroom participation with extra practice-prep points, which they use to boost grades at the end of every semester.

This is obviously easier said than done as teachers can’t pick and choose who they bend the rules for, but after being so close to the grade you strived so hard for, it’s hard for some students to be okay with a lower grade then they feel they deserved. Letter grades have begun to define our generation, even more than the actual work we do or what we learn. Colleges will see just a “C” on a transcript, not knowing or caring whether you got a 69.6% or a 79.45%, and your GPA will go down the same amount regardless of whether or not you would have worked a little less hard and gotten a 72 versus a 79%, leading students to care heavily about the letter grade they get, leading to teachers receiving tons of inquiries about bringing up grades.

Although difficult, some standard procedure should be in place for students who are so close and deserve the higher grade. If students thought they could just do their best, participate in the classroom and learn and it should be possible for their grades to be brought up, then schools could become a place more focused on learning rather than grades and GPAs, but that’s a whole different issue within our schools.

Shouldn’t be bumped

Baxter Roberts

MCPS is notoriously soft for grades. We get numerous safety nets to prevent us from suffering bad outcomes. On top of this, our marks are generally inflated. The semester grading system effectively erases bad results and gives students a second chance. With all these benefits, the selective nature of grade bumping is ridiculous and impractical.

Let’s start with the grade safety net. The most significant part of this system is the 50% rule, preventing students from getting zeros. All work, whether turned in or not, will receive, at the lowest, a 50%. This has a few serious consequences. If students are happy with their grades at the end of the quarter, they can simply stop trying. There is no more grade-related reason to continue putting effort into the class. It also means things like cheating and late work have a much smaller effect on the overall grade, making these two courses of action seem less risky.

Another major part of the safety net is the semester grading system. This system averages out quarter grades and takes the highest available option. An A and a B become an A, regardless of the percentage of that A/B. An A and C become a B with a similar result. Essentially, we get a second chance. We can erase a bad quarterly result with hard work in the next quarter, an extremely forgiving idea.

What does this have to do with grade bumping? In my mind, the safety net makes grade bumping feel frivolous and entitled. Complaining about percentage points on a grade feels ridiculous when so many systems are already in place to keep us afloat. At what point does the student become responsible for getting the grade they want by striving for it instead of being given it? The amount of free grade boosting built into the system is already enormous; adding something like grade bumping, which has inconsistent application, removes student accountability and drive for success.

Grade boosting, at best, is wildly inconsistent. Each teacher has a different policy on whether or not they boost grades at the end of each grading period. This, again, comes with a host of problems. Keeping track of every teacher’s boosting philosophy is near-impossible, with many other school-related things being more important. This lack of clarity leads to awkward, lose-lose interactions between teachers and students. The student feels wronged because they didn’t know if a given teacher would bump their grade, and the teacher feels exasperated because they feel like they made it clear. Eliminating the possibility of boosting in the first place would end these interactions.

Another element of inconsistency is favoritism. It’s no surprise that teachers favor certain students. This unconscious bias is never public, except for grade boosting. Subconscious favoritism can come to the forefront in teachers picking and choosing who they boost. This is no fault of the teacher, simply the system they work in. Without the possibility of grade boosting, teachers would never face this decision, and students would never feel slighted.

On top of all these reasons, eliminating grade boosting will make students work harder overall. Without the potential to beg for a better grade, students will be forced to plan ahead and study harder accordingly. The safety net is already there; this inconsistent addition actively removes work ethic.